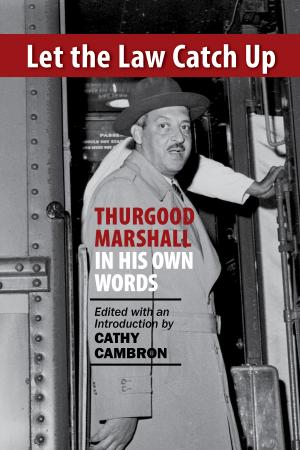

Let the Law Catch Up

Thurgood Marshall in His Own Words

ISBN 9781566494137 (paperback)

Published in March 2022

MSRP $14.00

"He was my model as a lawyer . . . I took a step-by-step, incremental

approach; well, that’s what Marshall did. He didn’t come to the

Court on day one and say, 'End apartheid in America.' He started

with law schools and universities, and until he had those building

blocks, he didn’t ask the Court to end separate-but-equal. . . . The

difference between Thurgood Marshall and me, most notably, is

that my life was never in danger. His was. He would go to a Southern

town to defend people and he literally didn’t know whether he

would be alive at the end of the day." – Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Thurgood Marshall persisted in the face of grave danger and wrested from the Supreme Court a series of stunning victories in the 1940s and 1950s that demolished the legal edifice of racial segregation in the United States. He summed up his indomitable attitude in 1969: “It takes courage to stand up on your own two feet and look anyone straight in the eye and say, ‘I will not be beaten.’” (Thurgood Marshall, speech at Dillard University) His record of successful appearances before the Supreme Court is still unbroken.

During Marshall’s 1967 Supreme Court confirmation hearings, segregationist senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina had asked Marshall whether judges should stick to “what was written in the Constitution.” He replied, “Yes, Senator, with the understanding that the Constitution is meant to be a living document.”

With its post–Civil War amendments designed to eradicate the stigma of slavery and create equality between the races, the U.S. Constitution promised much to Black citizens, but delivered little justice. Marshall spent his career as an attorney—as, indeed, the “greatest attorney of the twentieth century,” according to Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan, who clerked for him—determined to make the Constitution live up to its promises.

“You do what you think is right and let the law catch up.” Marshall’s remark that gave this book its title—that he believed in doing what he thought was right and letting the law catch up—reflected his lived understanding of the Constitution as a work in progress. It began its life as a very defective document; after all, it countenanced and facilitated the trade in kidnapped and enslaved human beings and ratified and enforced their continued captivity. But the Constitution, like the Union, has become “more perfect” through struggle, suffering, sacrifice, amendment, argument, and interpretation.

In January 2021, as Kamala Harris was sworn in to the vice presidency of the United States, she lay her hand on a Bible that had once belonged to her hero Thurgood Marshall. A courageous and brilliant lawyer and jurist, Marshall won the 1954 Supreme Court ruling ending legal racial segregation in America—a significant step in the continuing struggle of Black Americans for equal treatment in their own country. In 1967, Marshall became the first Black Supreme Court justice, and he continues to inspire us decades after his death.

This accessible collection of Marshall’s own words spans his entire career, from his fearless advocacy with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the 1940s and 1950s, to his arguments as the first Black solicitor general and his Supreme Court opinions and dissents. Introductions to the writings provide historical and legal context.

approach; well, that’s what Marshall did. He didn’t come to the

Court on day one and say, 'End apartheid in America.' He started

with law schools and universities, and until he had those building

blocks, he didn’t ask the Court to end separate-but-equal. . . . The

difference between Thurgood Marshall and me, most notably, is

that my life was never in danger. His was. He would go to a Southern

town to defend people and he literally didn’t know whether he

would be alive at the end of the day." – Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Thurgood Marshall persisted in the face of grave danger and wrested from the Supreme Court a series of stunning victories in the 1940s and 1950s that demolished the legal edifice of racial segregation in the United States. He summed up his indomitable attitude in 1969: “It takes courage to stand up on your own two feet and look anyone straight in the eye and say, ‘I will not be beaten.’” (Thurgood Marshall, speech at Dillard University) His record of successful appearances before the Supreme Court is still unbroken.

During Marshall’s 1967 Supreme Court confirmation hearings, segregationist senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina had asked Marshall whether judges should stick to “what was written in the Constitution.” He replied, “Yes, Senator, with the understanding that the Constitution is meant to be a living document.”

With its post–Civil War amendments designed to eradicate the stigma of slavery and create equality between the races, the U.S. Constitution promised much to Black citizens, but delivered little justice. Marshall spent his career as an attorney—as, indeed, the “greatest attorney of the twentieth century,” according to Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan, who clerked for him—determined to make the Constitution live up to its promises.

“You do what you think is right and let the law catch up.” Marshall’s remark that gave this book its title—that he believed in doing what he thought was right and letting the law catch up—reflected his lived understanding of the Constitution as a work in progress. It began its life as a very defective document; after all, it countenanced and facilitated the trade in kidnapped and enslaved human beings and ratified and enforced their continued captivity. But the Constitution, like the Union, has become “more perfect” through struggle, suffering, sacrifice, amendment, argument, and interpretation.

In January 2021, as Kamala Harris was sworn in to the vice presidency of the United States, she lay her hand on a Bible that had once belonged to her hero Thurgood Marshall. A courageous and brilliant lawyer and jurist, Marshall won the 1954 Supreme Court ruling ending legal racial segregation in America—a significant step in the continuing struggle of Black Americans for equal treatment in their own country. In 1967, Marshall became the first Black Supreme Court justice, and he continues to inspire us decades after his death.

This accessible collection of Marshall’s own words spans his entire career, from his fearless advocacy with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the 1940s and 1950s, to his arguments as the first Black solicitor general and his Supreme Court opinions and dissents. Introductions to the writings provide historical and legal context.